I won’t say that it’s weird, but it’s weird. Indian Wells, cancelled. Roland Garros, rescheduled. I have my fingers crossed for the Western and Southern Open, where I hope to see those of you who my Junior Tennis Star and I were delighted to run into last year. But I know that other folks have more serious matters to worry about, and I don’t mean to diminish what is occurring in the world by writing this article.

I offer you several movies, television shows, and novels for your Social Distancing Days, one of which involves tennis. Don’t search on Netflix. What Netflix’s algorithms offer are movies called “Pandemic,” “Outbreak,” and “Containment.” Not something I’m going to watch. Consider The French Lieutenant’s Woman, starring Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons. I am obsessed with Irons from Brideshead Revisited, one of my favorite novels of all time, written by Evelyn Waugh. Waugh’s novel is an extreme departure from his silly, slap-happy Bertie and Jeeves series of stories that were dramatized by PBS. Bertie Wooster was an early role for Hugh Laurie, of House fame. Brideshead Revisited is the best coming-of-age novel, even better in my opinion than Michael Chabon’s The Mysteries of Pittsburgh.

In the movie adaptation of Brideshead Revisited, Irons plays Charles Ryder, the upper crust Oxford student who meets and even upper-crustier Lord Sebastian Flyte. Flyte carries a teddy bear and introduces his coterie to the luxuries of fine wine and plovers’ eggs at Oxford, whilst trying to escape the watchful eye of the family’s priest-spy. Flyte and Ryder become bosom friends which relationship seems to teeter on a near- intimate one, but Flyte’s alcoholism eventually takes control, removing Flyte from his closest friend, his family, and society. Ryder, abject with the loss of his dear friend, suffering from a father who prefers artifacts to his son, and married to a hum-drum, society-climbing wife who doesn’t understand his artistic temperament, seeks solace in Flyte’s sister, Julia.

Julia has her own ghosts: she is tormented by her Catholic religion and a boor of a husband who she married out of rebellion (“It’s just that he isn’t a real person at all; he’s just a few faculties of a man highly developed; the rest simply isn’t there.”) Both Ryder and Julia toss off convention and engage in a long-term affair, seemingly to console each other for the loss of their respective friend and brother. Yet Ryder and Julia’s relationship never cements into a deep, sustainable love. Sebastian and Julia’s ancestral home, Brideshead, is the setting. The novel Brideshead Revisited has something – a turn of phrase, imagery in a scene, and even a turtle with diamonds set in its shell – which speaks to everyone, guaranteed. And the 1981 movie, relatively true to the text, will not disappoint.

The same for 1981 The French Lieutenant’s Woman, which is a two-fer movie, with two parallel and competing story lines – the movie story versus the real-life story. Irons plays an actor who plays Charles Henry Smiths. Henry Smiths succumbs to the crafty she-witch played by Streep, who the locals call the French lieutenant’s whore. Despite the local lore, however, Streep’s character is unblemished yet she revels in her social ostracism, eventually beguiling the obsessive Henry Smiths.

Irons playing the actor who plays Henry Smiths is equally obsessed with Streep’s actor-character, and he wants to leave his wife and family to live with her. Streep, also in a committed relationship, presciently knows that their relationship will end at the end of the filming of the movie. Confused? I’m not surprised. So watch the movie where you will learn that both of Streep’s characters control both outcomes; i.e., the women win. Leo McKern, of the Rumpole of the Bailey television series based on stories created by John Mortimer, with his wonderfully big, bulbous nose that makes him such a great character actor, plays a supporting role.

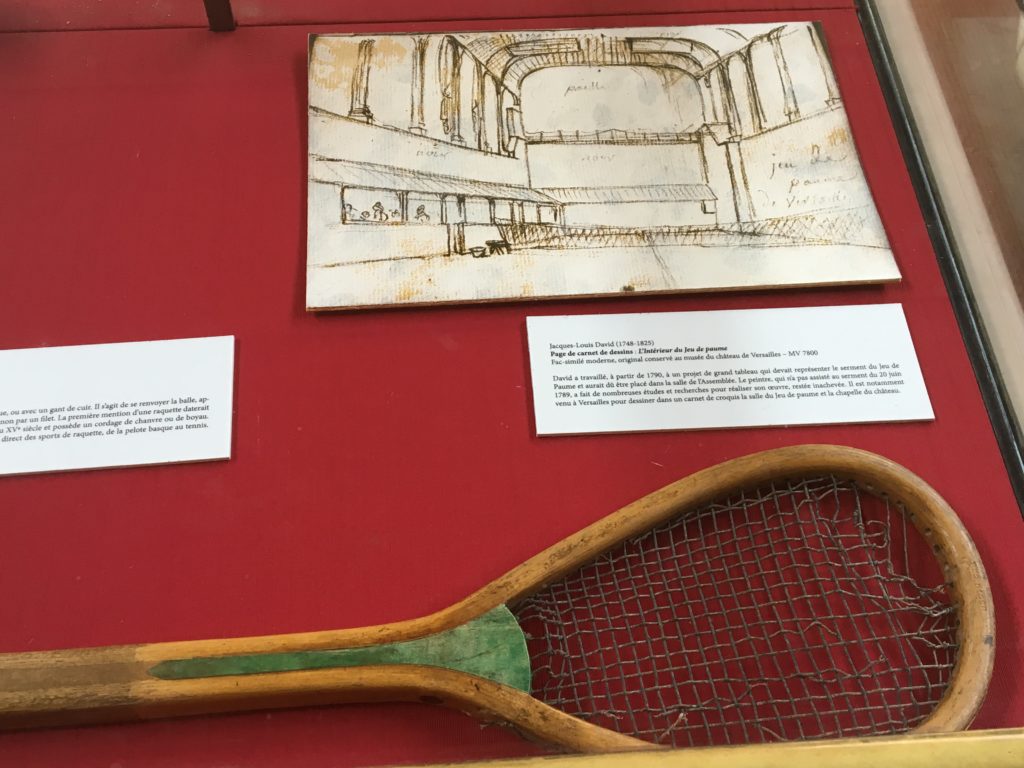

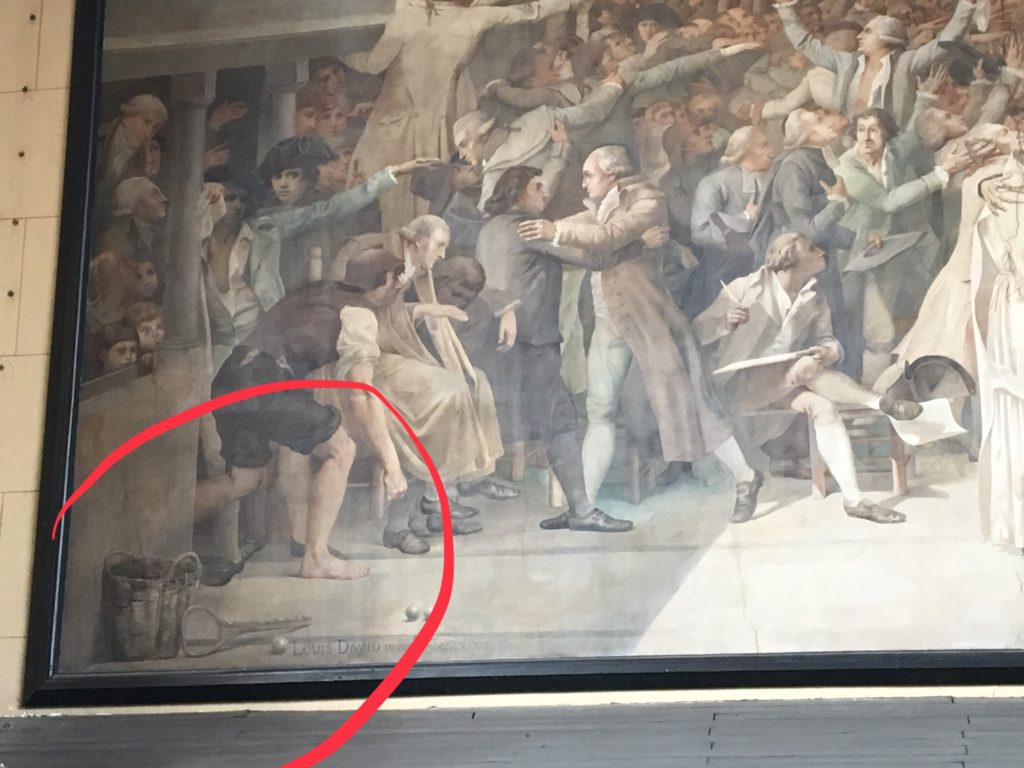

Court tennis or real tennis comes in when Henry Smiths consults his attorney about the lawsuit he is facing after breaking his engagement because of his obsessive love for the French lieutenant’s woman. For an explanation of court tennis, please see my article from last year here. Irons, with a racquet that looks true to the ancient game, takes out his frustrations and receives a dressing down from his solicitor, as they knock the balls off of the awnings of the real tennis court. Irons plays court tennis like Ryan O’Neal’s character Oliver Barrett, III in Love Story plays squash. The court for both becomes the vehicle for their emotional expression. Barrett plays well when life is good; he falters when Jenny is dying. Did you know that Erich Segal wrote the novel Love Story as a companion for the movie?